The sacredness of “bread & salt” was manifested in the customs of our Slavic ancestors. Thus, in Russia there was a ban on swearing and lying if bread & salt were on the table. And to confirm the truthfulness of the oath, the Russians pronounced “honest bread and salt”, and the Bulgarians “хлеба и солта ми” (“my bread and salt”). Hence the idea of the purifying properties of “bread-salt”: in Polesie region they were placed in “dezha” (special wooden tub for sourdough bread making) to cleanse it; in Ukraine they were given to a woman prior to the first visit to church after giving birth, etc.

ꏍ

“Bread and salt” were widely used in wedding ceremonies. Among the Eastern Slavs, Bulgarians, Poles, matchmakers came to the bride’s house with bread and salt. If the offer of the matchmakers was accepted, the bride’s parents gave them bread and salt in return. The closest female relative or matchmaker circled three times with bread and salt around the parents’ hands, securing the decision on the engagement. Then the matchmaker broke the bread, saying: “The deed is done and sealed with bread and salt” (Yaroslavl region).

ꏍ

With the blessing of the groom and the bride, the Belarusians used to say: “I bless you with bread, salt, happiness, destiny and good health”. The Bulgarians wished the engaged couples to stay together like bread and salt. In Poland, the newlyweds at home after the wedding walked around the table three times with bread and salt, after which the wife kissed the corners of the table and put the bread on the “pech” (the fireplace for cooking and heating).

ꏍ

To be continued…

Bread and salt – part 1

Among all Slavic nations, the pair of “BREAD & SALT” since ancient times has become a symbol of hospitality, harmony, home well-being, prosperity, sacredness and purity. Traditionally, to maintain the well-being of the home, bread and a salt were always present on the table. Czech proverb: “Chléb a sůl zdobí stůl” (“Bread and salt decorate the table”). And the Russians used to say: “There is no lunch without bread and salt.” It was customary among all the Slavs, when setting the table, to first put bread and salt, and then the rest of the food.

ꏍ

Bread and salt were a symbol of hospitality, thus it was almost mandatory to offer them even to an enemy – the Poles had a saying: “Złemu wrogowi chleba i soli” (“Bread and salt to an evil enemy”). When meeting a guest, the hosts brought out bread with a salt cup on a towel or tablecloth. Refusal of bread and salt was greatly condemned: “Kdo u nás chleba a soli nepřijme, ten není hoden, abychom mu židli podali” the Czechs used to say (“Whoever does not accept bread and salt from us – is not worthy to be given a chair”).

ꏍ

The pair “bread and salt” among the Slavs also became a symbol of harmony. Bulgarians used to say: «като сол и хляб»; Serbs: «слажу се као хлеб и со»; Poles: “chleb z solą znak i hasło zgody” (“bread and salt – the sign and motto of agreement”).

ꏍ

To be continued…

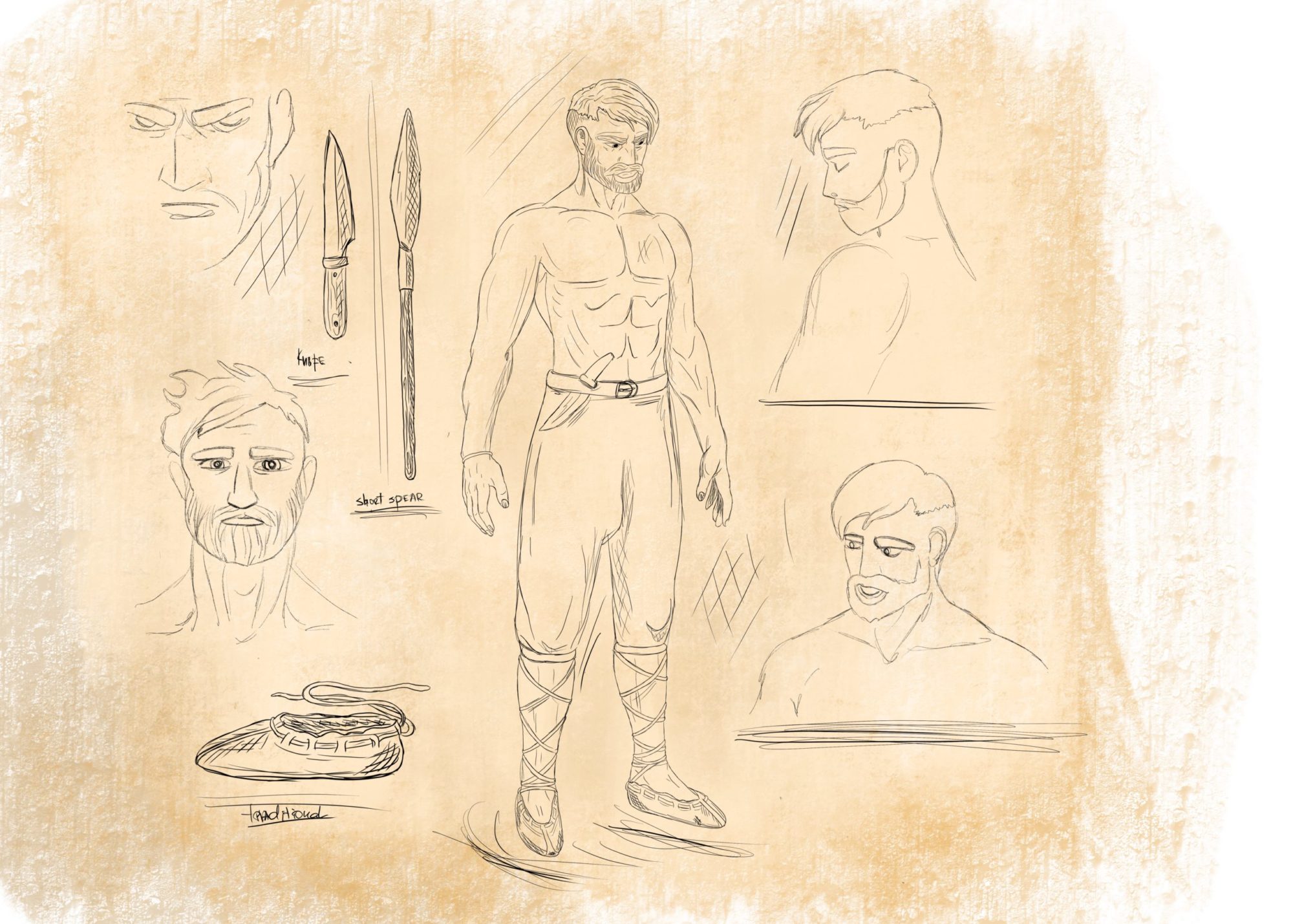

“Maurice’s Strategikon” – Part 3

As a conclusion of a series of posts about the “Maurice’s Strategikon”, see below a note on the famous Slavic hospitality 😀🎂🍽🥂, as well as the ancient art of disguise, which the author considered important and necessary to mention.

ꏍ

“They are kind and hospitable to travelers in their country and conduct them safely from one place to another, wherever they wish. If the stranger should suffer some harm because of his host’s negligence, the one who first commended him will wage war against that host, regarding vengeance for the stranger as a religious duty.”

ꏍ

“Their experience in crossing rivers surpasses that of all other men, and they are extremely good at spending a lot of time in the water. Often enough when they are in their own country and are caught by surprise and in a tight spot, they dive to the bottom of a body of water. There they take long, hollow reeds they have prepared for such a situation and hold them in their mouths, the reeds extending to the surface of the water. Lying on their backs on the bottom they breathe through them and hold out for many hours without anyone suspecting where they are. An inexperienced person who notices the reeds from above would simply think they were growing there in the water.”

ꏍ

For more interesting facts refer to the source: “Maurice’s Strategikon: Handbook of Byzantine Military Strategy”, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2001

ꏍ

The “Maurice’s Strategikon” – Part 1

The “Maurice’s Strategikon” is one of the earliest sources about the Slavs. The creation of this Byzantine military handbook is attributed to the emperor of Mauritius in the late 6th – early 7th centuries.

ꏍ

The ” Strategikon ” pays much more attention to the Slavs than to other nations and considers them as a strong military enemy of the empire. First of all, it talks about the tribes that lived on the northern bank of the Danube. From this source, we can learn a lot of interesting facts about our Slavic ancestors.

ꏍ

“The nations of the Slavs and the Antes live in the same way and have the same customs. They are both independent, absolutely refusing to be enslaved or governed, least of all in their own land. They are populous and hardy, bearing readily heat, cold, rain, nakedness, and scarcity of provisions.”

ꏍ

“They do not keep those who are in captivity among them in perpetual slavery, as do other nations. But they set a definite period of time for them and then give them the choice either, if they so desire, to return to their own homes with a small recompense or to remain there as free men and friends.”

ꏍ

To be continued…

Pants in Slavic tradition – Part 2

The old photograph of the last century depicts a barefoot Russian peasant who sows linen, while carrying seeds in his pants instead of a bag or basket. Why do you think he is doing it like that?

ꏍ

This ancient Slavic tradition of ensuring the plentiful harvest of flax came to us thanks to the Soviet anti-religious propaganda marked as “savage ritual” 🙂 So what is really shown on the picture?

ꏍ

The producing fertility power was attributed to the pants, so they were constantly used in maternity, wedding, agricultural and cattle breeding ceremonies by Slavs. In the Ryazan region, while sowing, the owner carried seeds in his own pants. Polish people believed that “double” ears (spica) could grow from grains passed through the pants of the sower. In Kaluga region cannabis seeds were poured into special pants so that cannabis would be stronger, these pants were carried on the shoulder, and after sowing, they were hung in a barn on a high hook – so that cannabis “would be poured to the top”. By the way, hemp/cannabis was used to make the best ropes very popular among the sailors and at some point, Russia was supplying the whole world with these ropes for ships 😉

ꏍ

To attract grooms and matchmakers to the village, in the Volga region around New Year people stole pants from someone’s backyard where clothes were drying, and then dragged them around the village. In Polesie, a family which had a girl of marriageable age, would draw a circle around their house with pants, so the girl would get married. Men’s pants were tied to the table during the matchmaking, so that the bride would agree to marry.

ꏍ

Source: “Slavic Antiquities” – encyclopedic dictionary in 5 volumes by Institute for Slavic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

Photo: Museum fund of Russia https://goskatalog.ru/