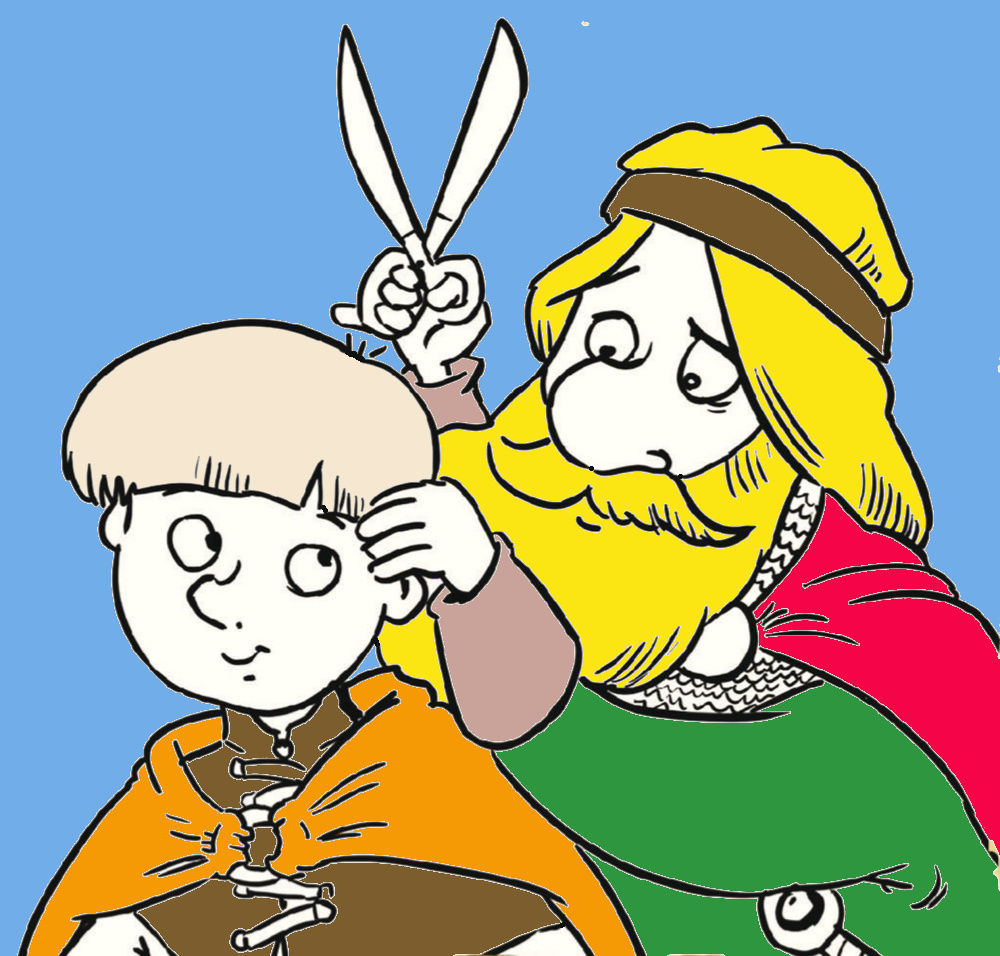

Postrizhiny in early childhood were common among all Slavs. The ceremony mainly extended only to boys, but sometimes to children of both genders – and was supposed to provide the child with good development, a happy fate, timely marriage, wealth, etc.

ꏍ

Most often, postrizhiny were done at home by the fireplace with a child sited on a table. The Eastern Slavs could also put child on a bench in the “red corner”. In Bulgaria, the child would be standing on dezha (special wooden tub for sourdough bread making) facing east. Ukrainians would sit the child on the fur coat. A spinning wheel, a comb, threads were put under the fur coat when cutting a girl’s hair, and when cutting a boy’s – a knife, a jointer, scissors, thereby wishing the child to acquire professional skills.

ꏍ

The method of cutting the first hair strands and the accompanying magical practices differ in various Slavic traditions. For example, among the Bulgarians, the one who cut the hair, washed the face of the child with water from a new jug, then “cut” the air with scissors and said (literally “glorified” – a verb derived from “slava”): “So that you grow old and gray, like Stara Planina (Balkan Mountains) and like your grandfather in old age”.

ꏍ

What rituals associated with the first haircut of children do you know?

ꏍ

To be continued…

ꏍ

Postrizhyny in Slavic tradition

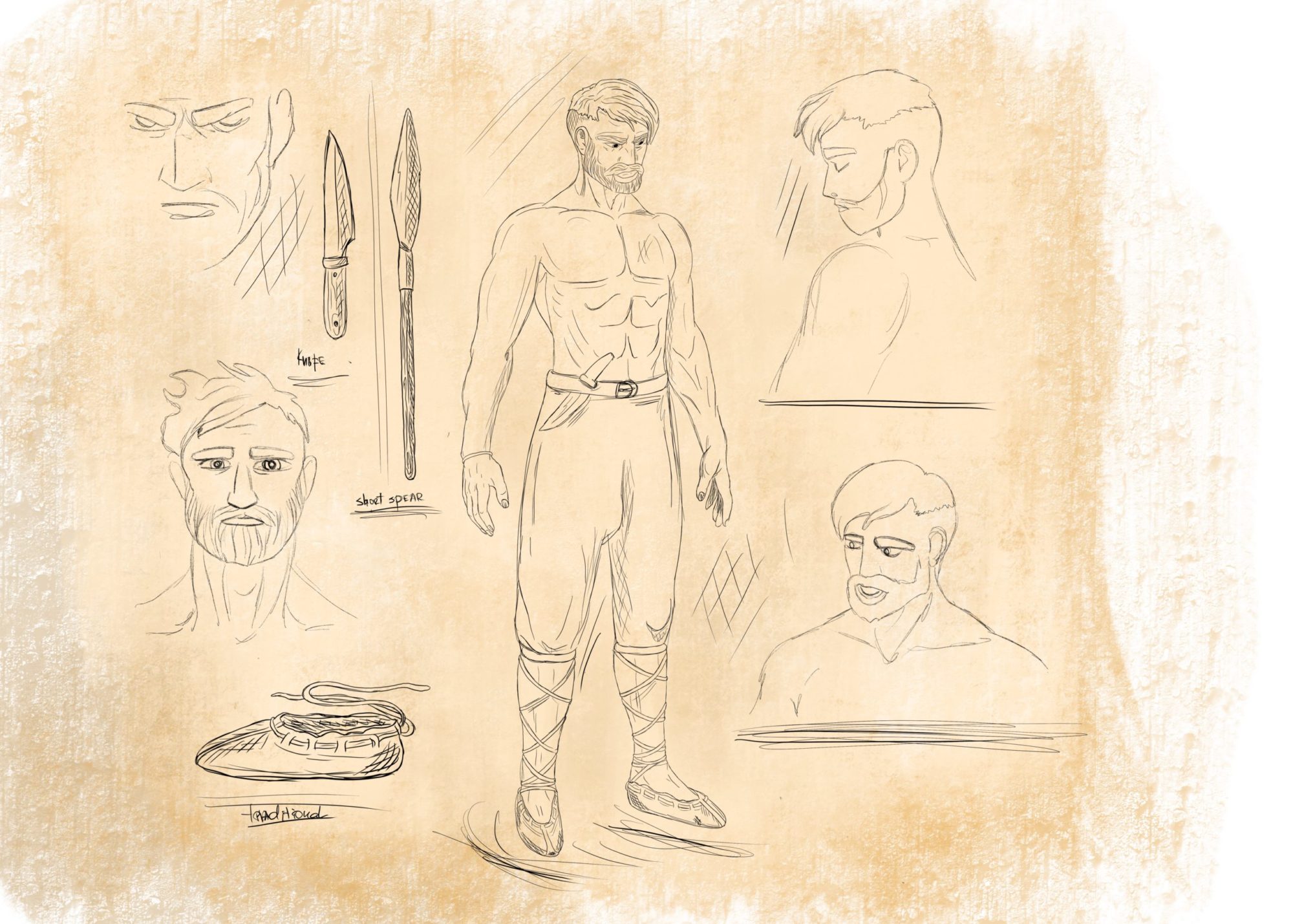

Postrizhyny is the ancient Slavic ritual of the first haircut for a boy. In Serbia and Montenegro it was called “стрижене”, in Russia “пострижины”, in Bulgaria and Macedonia “стрижба”, in Poland “postrzyżyny”. This rite included cutting off strands of hair, magical rituals with it, dressing up a child in new clothes, exchanging gifts, good wishes, fortune-telling about the future, etc.

ꏍ

For Russians, the ritual hair cutting coincided with the beginning of the teachings – the knowledge transfer from the adults. Postrizhyny marked the recognition of the child as a person. Written sources testify about postrizhyny of 5–7-year-old sons of the nobility, which had an initiatory character and reflected family ties and customary law. For example, postrizhyny of Yuri and Yaroslav, the sons of the East Slavic duke Vsevolod (years 1192 and 1194), as well as the Czech duke Václav. After the ritual haircut, the prince was put into the saddle of his father’s horse, “so that he could step into his father’s stirrup”, in other words to follow his father steps. This meant the recognition of the son by the father. Also, the father’s shirt was put on him, and the whole ceremony was followed by a feast. Gallus Anonymus also describes postrizhyny of the legendary founder of the Polish Piast dynasty – Siemowit.

ꏍ

And how was the first haircut for you or for your children?

ꏍ

To be continued…

Artist: Małgorzata Lewandowska https://www.instagram.com/art_by_goria/

https://www.facebook.com/ArtByGoria

ꏍ

Polevik can be kind

In Slavic beliefs, Polevik is a hostile creature but sometimes he helps humans. Novgorod people believed that Polevik could warn field workers about danger – for example, drive them out of the field before an approaching thunderstorm.

ꏍ

That is why people always tried to please Polevik. In Novgorod, when pasturing cows in the meadowland, people bowed to Polevik and said: “Field father, field mother with little children, take my cattle, give it water and feed it”. And when cattle got lost, people would take bread and three coins, stand on the road and say: “Master of the field, I will give you bread and a gold treasure, and you bring my hog home.”

ꏍ

In the Oryol region of Russia, on certain holidays at night, a couple of eggs and an old rooster stolen from neighbors were sacrificed to Polevik in the field. It was believed that, without a sacrifice, Polevik would get angry and destroy all the bread in the field. And in the Yaroslavl region, at the end of the harvest people left several uncut bread spikes as an offering to Polevik.

ꏍ

Why do you think they sacrificed not their own, but the neighbor’s rooster? 😉

Artist: https://www.deviantart.com/natale777

ꏍ

More interesting facts can be found in: “Slavic Antiquities” – encyclopedic dictionary in 5 volumes by Institute for Slavic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

ꏍ

Polevik can be evil and grumpy

Polevik in the beliefs of the Slavs is an evil, grumpy and unpredictable spirit. He scares people with his sudden appearance, wild echo, clapping his hands or whistling, and also takes the form of a monstrous shadow that chases people. Russians and Ukrainians believed that Polevik makes people to go astray (especially children who go to the fields for flowers), “leads” them through the fields and lures them into a swamp, or makes fun of drunken plowmen. He can drive an entire wedding procession into a river. Polevik could pester to a traveler with questions: “How are you? Where are you going? Why?”, which would knock people off their way.

ꏍ

Belarusians in Vitebsk region believed that, if Polevik got angry – he tormented the animals grazing in the field by sending flies and horseflies on them. Or he could trample down the crops, or twist the plants, or send damaging insects and harmful winds on them. He could also deflect the rain from and bring the cattle to the crop fields. In Ukrainian beliefs, Polevik himself sows weeds in the fields. Russians of Smolensk region had a saying about the cause of the cattle illness: “Polevik flew into the ear”. Russians also believed that even Polevik’s children (‘Mezhevichki’) run along the field borders, catching birds and strangling people who dare to lie there.

ꏍ

What a family! I wonder what his wife is capable of? 😉

ꏍ

To be continued…

Artist: Ivan Tsygankov

ꏍ

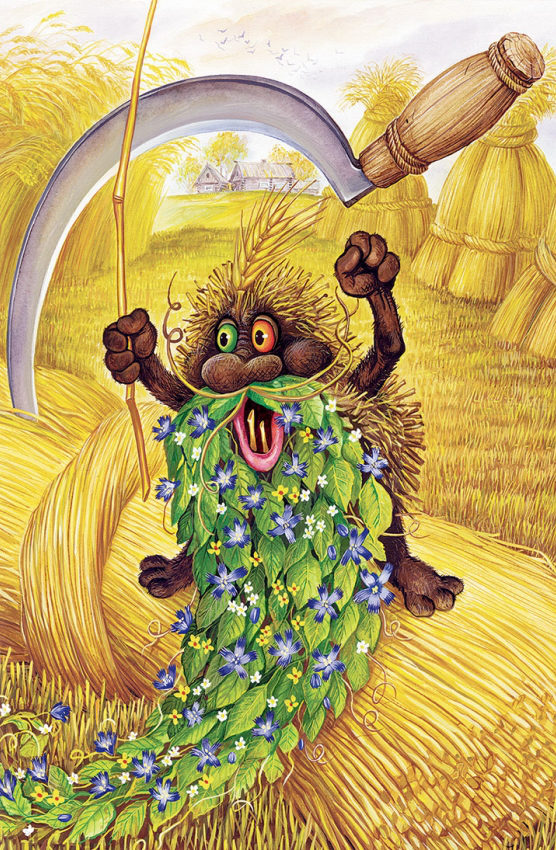

Polevik – the appearance

In Southern Russian beliefs, Polevik is the personification of the field – naked, black as the soil, eyes of different colors, long green grass instead of hair, a beard of stalks, and he himself is a little ugly old man.

ꏍ

In the northern Russia regions, Polevik was imagined as a young man with very long legs. He is covered with fiery hair, has bulging eyes, horns and a long tail. Polevik uses his tail’s bushy tip to raise dust from the ground if he does not want to be seen.

ꏍ

Eastern Ukrainians believed that Polevik is covered with fur, has small horns and ears like a calf. But he can only be seen while asleep. In Kharkov region people imagined him as white as snow with a white beard. In Novgorod region in Russia – that he has grey hair. In Vologda region – that he simply dressed in white clothing, and that he can run very fast. So fast, that he seems to a person like a flashed spark.

ꏍ

Polevik can also change appearance: during the day he looks like a little man, and at night – like a flickering light. He can change his height, turn into a young or old person, or even a familiar neighbor.

ꏍ

So how can one recognize Polevik in a neighbor – any thoughts? 😉

ꏍ

To be continued…

Artist: Anastasiya Lysenko https://www.instagram.com/sstu.arto/

ꏍ